It’s not surprising that most of us have heard of soju, but contrary to popular belief, Korean alcohol is not just limited to that drink in that ubiquitous green bottle, there is also makgeolli. While both are Korean alcoholic beverages and made primarily from the same three ingredients (steamed rice, water and nuruk, the traditional Korean fermentation starter); their origins and popularity differ.

We can thank hallyu (aka the Korean wave) for introducing Korean pop culture by way of BTS, Crash Landing on You and kimchi. But the world is also now privy to Korea’s rich history and culture as well as the many trends which permeate our modern life. Trends such as the 12-step Korean beauty routine or mukbangs have become topics of intrigue to outsiders, but there’s also a revival in other much beloved Korean inventions such as makgeolli.

Makgeolli is a milky, sweet and slightly fizzy alcoholic beverage currently enjoying a resurgence in popularity. To the uninitiated, the relatively low ABV (alcohol by volume) drink at 6-8% is an exciting new flavour and texture profile that is also an incredibly easy drink to have. But in earnest, it is hardly a new creation. As a matter of fact, it is regarded as the oldest alcoholic beverage in Korea!

What is Makgeolli?

First things first, what’s in the name? Makgeolli is made up of the Korean words ‘mak’ which means ‘roughly’ or ‘carelessly’ and ‘geolli’ meaning ‘to strain’ or ‘to filter’. Its name is very plainly derived from the method of how it is made. Cooked sweet rice and water is mixed with nuruk, a dry cereal cake made up of wheat, barley and rice which also carries bacteria, wild yeast and koji mould spores. This mixture is left on its own for a week in clay pots, for the nuruk to break the rice down into simple sugars which then turn into alcohol.

At this point, the sweet mixture is now at a relatively strong ABV of 15-19%. As this mixture settles, a top clear liquid is separated resulting in cheonju (refined rice wine) which is then distilled to become soju. It is the remaining settled sediment at the bottom that is diluted with water and then roughly strained – thus describing the name of the drink and how it is made.

Other names for makgeolli include ‘nongju’ meaning ‘farmer’s wine’, highlighting its historically popular alcoholic beverage of choice among farmers. The synonymous nature of this Korean alcohol to the agricultural working class has also contributed to the symbolic social divide of Korean alcoholic drinks between soju and makgeolli – with soju being made from the clear liquid off the top and makgeolli being made from the remaining opaque sediment at the bottom.

The hyperlocalisation of makgeolli

Consuming makgeolli fresh after a week will give it a milder and creamier taste. Due to its ingredients and properties, makgeolli technically does not perish or go bad. Still, it does continue to ferment developing a stronger taste and turning into rice vinegar after a few months.

Most of our first encounters with the drink would be in a Korean restaurant in off-white plastic bottles. But after learning about its brewing process and in order to retain its flavour for shelf life, most of the mass-produced makgeolli is pasteurized to stunt the drink’s growth and fermentation. As it is, the fermentation does not stop once bottled unless pasteurized.

This may allow for ease of transportation of the drink, but in return, manufacturers will have to opt for one-note sweetness over the complexity of fresh fermentation. Without pasteurization to impede fermentation, this could lead to causes in other problems in transit, such as bottles exploding due to over-fermentation and fizz.

With that, makgeolli like kimchi found its roots as a Korean household staple with each mastering their own technique and recipe. Each fresh brew differs in taste and fizz. (Think of other drinks that require starters and fermentation like kombucha and beer – flavours also differ for them due to the brewing time and process. There’s only so much you can standardise in a process – the rest must be left up to nature doing its thing.)

The rise and fall and rise in Makgeolli’s popularity

Despite not being as well-known as soju outside of Korea, makgeolli has a much deeper history of its existence. While its lack of popularity and ubiquity is due to the country’s banning of any and all home brewing production of alcohol, its story also carries with it the scars and consequences of war. But above all, it is exactly its accessibility that caused its banning. This is due to the simplicity of its making as mentioned above: most Korean alcoholic beverages can be made at home and with staple ingredients.

War, colonisation and extreme poverty are what essentially obliterated the ubiquity of makgeolli – starting with the Japanese colonisation that encompassed the two World Wars (from 1910 to 1945). By 1934, homebrewing was outlawed and before that, making alcohol required heavy taxes and licenses – even for personal consumption.

Following the Japanese occupation and the Korean war, the country was left in shambles. At this point, the focus was more towards rebuilding the country, and that included addressing a dire food shortage and the overall destitution of its people. So, on top of the ban on homebrewing, in 1960 another ban was introduced: using rice to produce alcoholic drinks was prohibited. Rice was a key ingredient for both soju and makgeolli so, it would seem like a no-brainer that the rice supply should be kept for nutrition rather than made into something to get drunk on. (As a result, manufacturers tried to use wheat or barley to replace rice in the making of these alcoholic drinks but that did not take hold.)

As the country slowly rebuilt itself, with the rice supply finally overtaking consumption, the ban on using rice to make alcohol was finally lifted in 1989 – almost 30 years later. And homebrewing was finally made legal again in 1995 – about 60 years later. As these are whole generations of time, much of the tradition was lost but the love for drinking helped with its comeback.

Korea’s Drinking Culture

Koreans love drinking. Back in 2018, news reports said South Koreans drink approximately 10.9 litres per person per year on average. No other country comes close to their per capita consumption.

If you make friends with locals during your trip, they will likely suggest a round of drinks. Drinking is part of Korea’s culture and the saying is, if someone invites you for a drink – soju or makgeolli – it is because that person wants to get to know you better. Take note that if someone older than you offers you a glass of alcohol, you should accept every glass. See the gesture as a compliment. However, Koreans will understand if you don’t drink for certain reasons so if you don’t want to drink the night away, politely say no.

Make sure to accept your drink with both hands. Also, use both hands if you are pouring drinks but make sure that you don’t pour your own drink. Worried about a massive hangover? Don’t fret. Since Koreans are big drinkers, they also have a wide range of hangover cures.

Korean hangover cures tend to start with haejangguk, i.e., ‘hangover soup’. n Korean, haejang means “detoxify” while guk translates to “soup.” Haejangguk recipes vary by region but usually consist of dried napa cabbage, vegetables and meat in a hearty beef broth. One of the most famous varieties is the kongnamulguk (bean sprout soup) from Jeonju, North Jeolla, which is made with a light seafood broth, bean sprouts, egg and seaweed.

Bean sprouts are said to rid the body of acetaldehyde, a chemical that causes hangovers. Haejangguk is so popular that just about every neighbourhood has at least one eatery serving this spicy hot soup. For many first-timers, this soup gives a surge of energy and makes them sweat.

If you prefer something cold, look for hangover ice cream known as Gyeondyo-Bar. This grapefruit-flavoured ice cream can be found in Withme FS, a convenience store chain that created this ice cream “to provide comfort to those who have to come to work early after frequent nights of drinking.”Gyeondyo-Bar can be roughly translated to the “hang-in-there-bar. In the middle of this bar is frozen Hovenia dulcis juice, a hang-over cure in traditional Chinese medicine.

After a hot bowl of soup and ice cream, head to a Korean-style spa known as jjimjilbang. These are 24-hour facilities with steam rooms, hot tubs, saunas and sleeping quarters! So sweat out more toxins and sleep the night away. Also drink Sikhye, a popular jjimjilbang beverage, made from rice, and said to shorten hangovers.

Makgeolli Breweries to visit in korea

One of the more well-known breweries is the Shinpyeong Brewery, one of Korea’s oldest family-run makgeolli breweries, spanning four generations. The brewery is in Dangjin which takes you on a tour of the company’s history and evolution over the years and finally a lesson on making makgeolli. This is offered by The Sool Company, which was founded by Julia Mellor, the first non-Korean specialist and a “self-confessed devotee to the makgeolli cause”. The Sool Company is a dedicated resource for all Korean traditional alcohol, and also offers online makgeolli brewing courses!

Another brewery making a splash is Together Brewing in Yeonhui-dong, Seoul. Founded and owned by Choi Woo-tack, the makgeolli is made with unlikely flavours such as plum blossom, mint and yuzu and other flavours in the works such as a milk-tea flavoured makgeolli. The brewery also has a makgeolli-making workshop where participants can explore the basics of mixing the nuruk with the rice and flavouring ingredients of their choice.

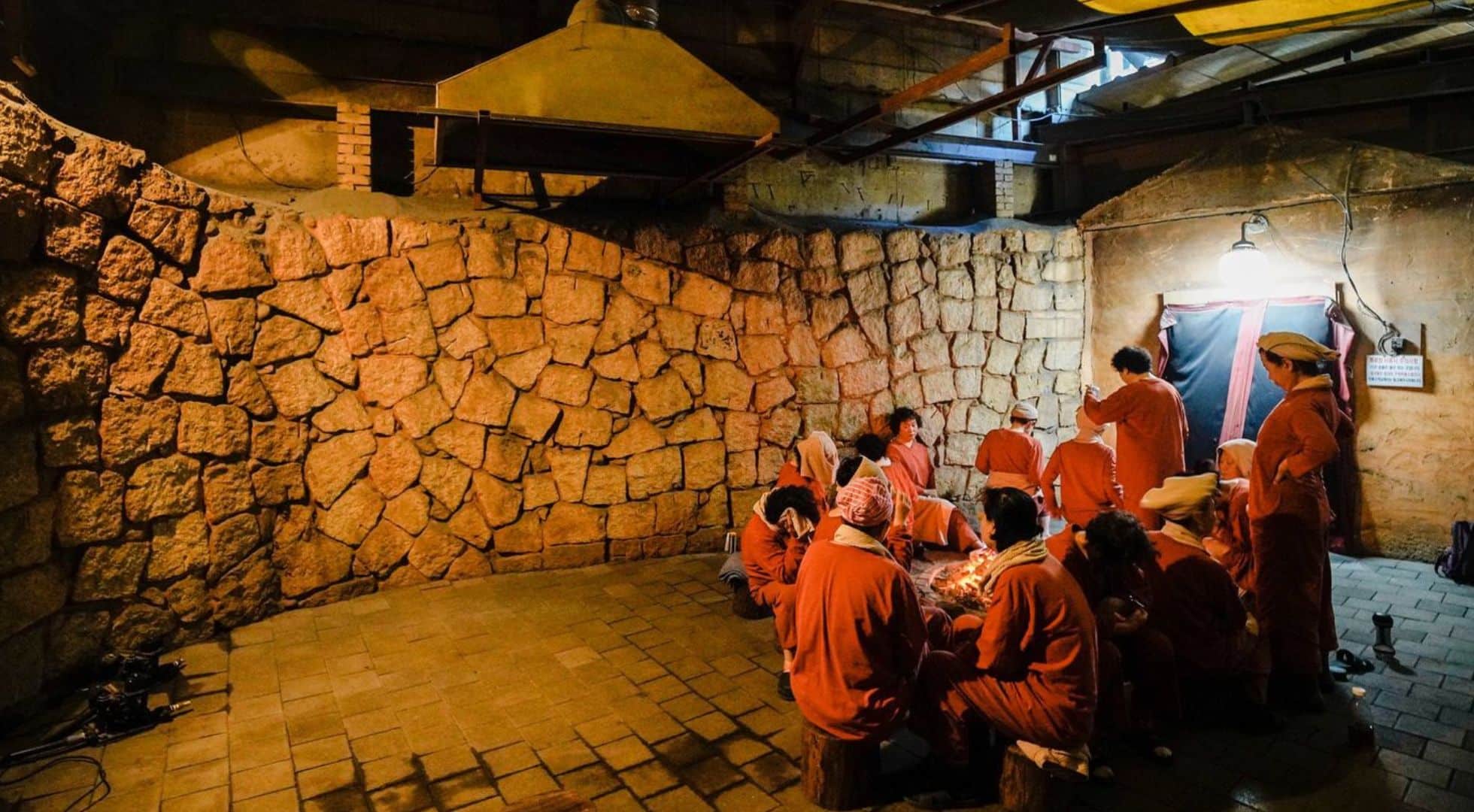

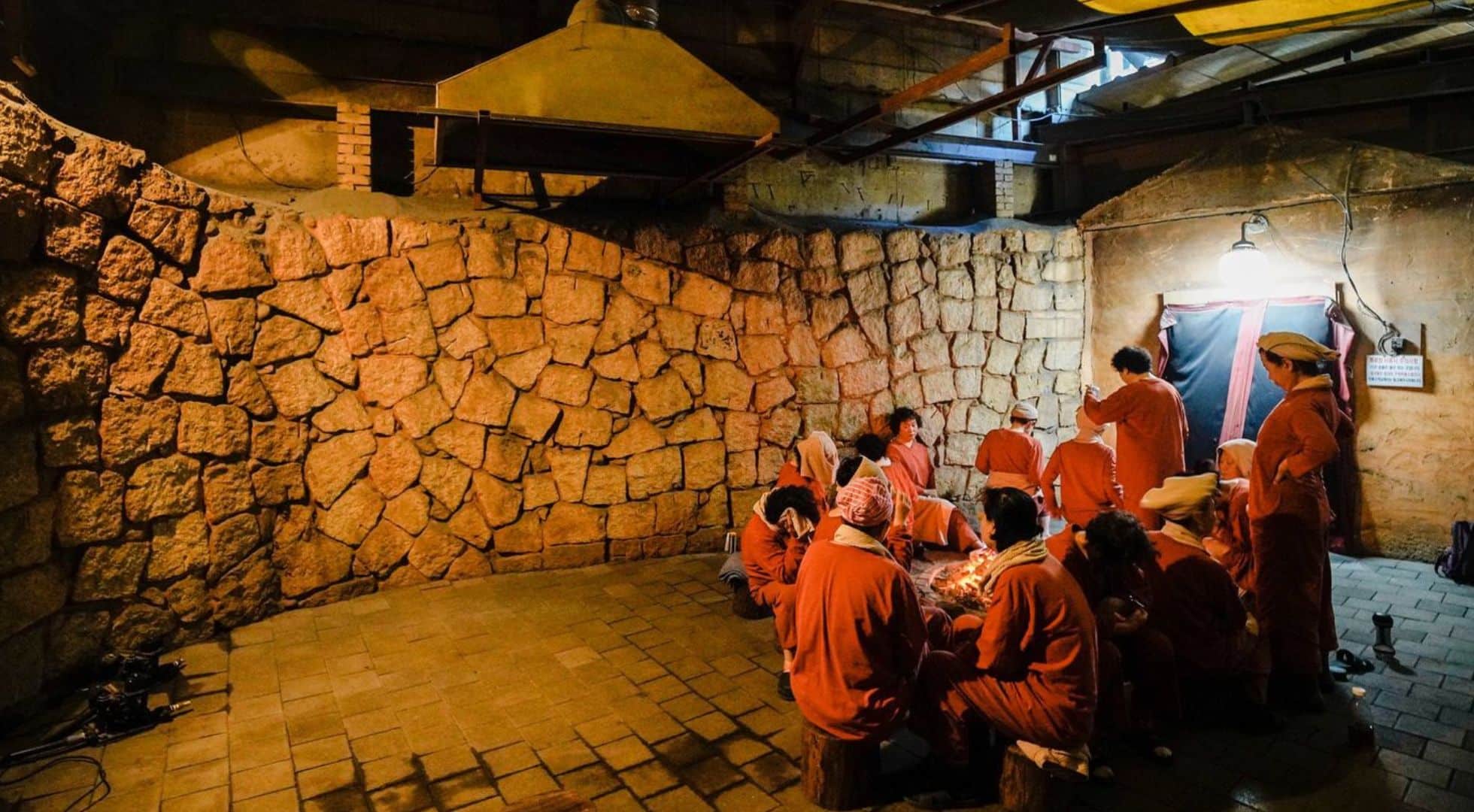

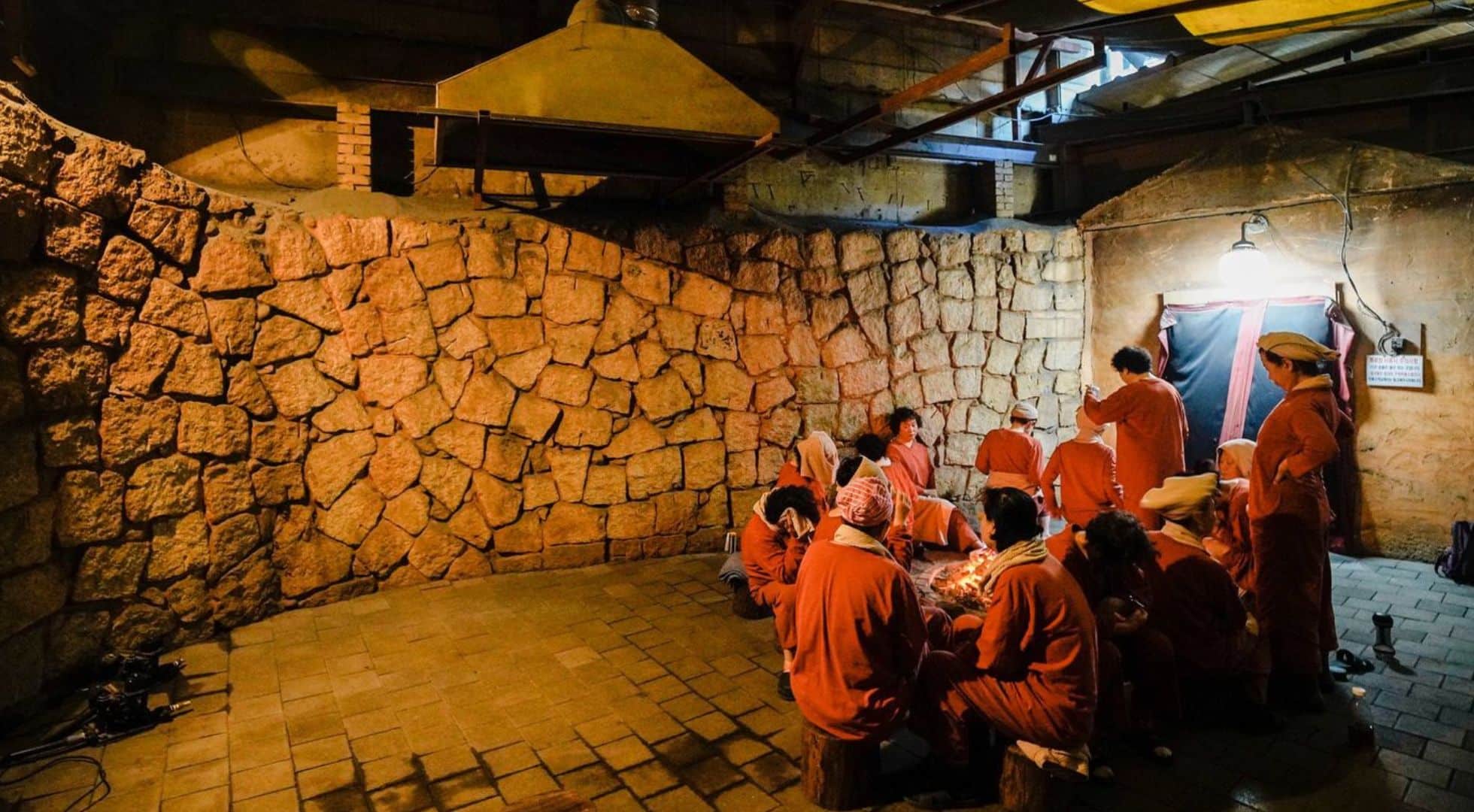

If you would like to just drink makgeolli, there are many trendy makgeolli bars all over Busan. Yong Ggum (literally translated to ‘dragon’s dream) is a favourite due to its location and is also known as a Cave Bar as it was once a bomb shelter. Otherwise, wander through Nampo or Seomyon neighbourhood to stumble into one of the many bars where makgeolli is available.

Makgeolli vs soju: when and how to drink it?

Korean alcoholic drinks are a perfect compendium to their cuisine; to complement the tart and zesty kimchi, to wash down the greasy and strong flavours of barbecues and gojuchang marinade and stews or to pair it with a freshly fried pajeon (green onion savoury pancake). It is said that the fizzy nature of makgeolli and its sweet, milky flavour serves as a great palate cleanser while snacking on heavy fried bar food.

While soju is poured into a small shot glass, makgeolli’s traditions hark back to the time when a small cup to imbibe just would not be enough. Its low ABV also means it can be drunk in large amounts. Makgeolli is not a sipping drink, thus a small bowl would make it more appropriate to take a big swig from. As the alcohol is made in clay pots, the traditional form was that it used to be ladled out from these pots into earthen bowls.

Now, in modern times, makgeolli can also be found served in aluminium kettles with matching huggable bowls big enough to gulp from. These days, this adds to the hipster look, often favouring the nostalgia and retro vibe which completes its story from its past to the present.

Finally, makgeolli is always served cold and drunk straight up, with no other additions or flavourings, although there have been experiments to add new flavours and add them into cocktails. The pot is swirled (or the ladle is stirred) to incorporate the sediments of the drink before pouring (or ladling out); the drink is then filled to the brim of your bowl, and you bring it up to your mouth taking a big gulp. The sweet, sour, milky, fizzy drink will undoubtedly be like nothing else you’ve had before!

Planning Your Holiday To Try MakGeolli and eat your way around korea? Let us help!

REACH OUT TO US at +603 2303 9100 or

[email protected]

You may also be interested in: